- Share via

One of the things that struck me while watching “Bonjour Tristesse,” written and directed by the celebrated author Durga Chew-Bose, was a feeling of being — and I don’t know how else to put it — tenderly haunted. Maybe it’s because Chew-Bose is an old friend of mine (we lived in the same dorm our first year of college), and the tenderness that exists between old friends imbues their experience of each other’s art. But others have also picked up on the ethereal, captivating quality of her adaptation of the 1954 French novel of the same name, written by Françoise Sagan. The film’s world is luscious, tangible and hypnotic.

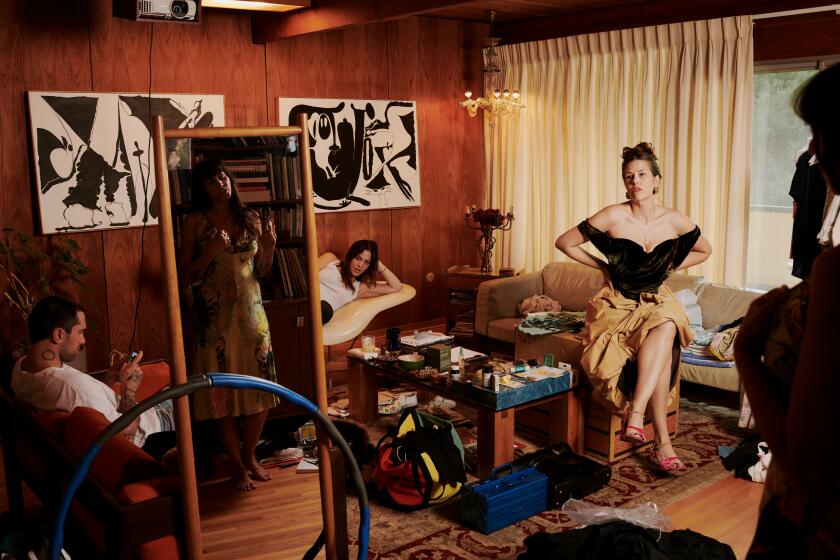

This hypnotism is especially conveyed through the film’s costumes. Chew-Bose — whose tenure in the fashion industry as managing editor of SSENSE gave her a nuanced insight into storytelling through clothes — worked with the renowned costume designer Miyako Bellizzi (“Uncut Gems,” “The History of Sound”) on the film. The result of their collaboration is a sartorial aesthetic that feels somehow outside of time. The costumes are, on the surface, contemporary: We see an Adidas sweatshirt here, a clingy party dress there. We know we’re in the present moment, but certain details pull us back in time. Kitten heels and full skirts, capri pants and tailored menswear, blouses with crisp collars and one-piece bathing suits feel less like “now” and more like “back then.”

Chew-Bose and I talked over Zoom about how, and why, costumes do so much heavy lifting when it comes to cinematic storytelling. The film, which is now playing in theaters, has a stellar cast, including Lily McInerny as the protagonist Cécile, her love interest Cyril played by Aliocha Schneider, Chloë Sevingy as a fashion designer named Anne, and Claes Bang as Raymond, Cécile’s father.

Eugenie Dalland: A costume designer recently told me that costumes are often the first place where storytelling begins in a film. What do you think about this idea?

Durga Chew-Bose: Miyako [Bellizzi] was showing me photos recently of Paul Mescal on set for a film she costumed — he’s standing in a forest wearing a period costume. She was like, “the only way you know what century this takes place in is because of my work.” She’s dispatching information through every costume choice she makes, every detail. Basically, everyone’s job on set is to give information to the image, and the costume design, for a lot of people, is where it begins. I thought that that was an interesting way to think about costume — as not just decor, but as a missive that tells you who, what, when, where, how.

ED: Let’s talk about the opening shots of “Bonjour Tristesse.” We see a close-up of the nape of a young man’s neck as he’s pulling off his T-shirt; he’s wearing a silver chain. Next, a close-up of a young woman lounging on a beach in a yellow one-piece bathing suit. What information were you dispatching with these shots?

DCB: I always wanted the opening shot to be of a young man taking his T-shirt off. That exact frame is so iconic for many people’s memories of summer. Immediately, we think: youth, summer, beach. I’d written in the script that the camera is very close to his body, not necessarily for the purpose of the female gaze, though obviously the shot is from Cécile’s point of view. I wanted to figure out what was the detail that felt like the quintessential guy’s detail. I asked Aliocha, “How do you take off your T-shirt?” Because most women I know take off their T-shirts like this [Chew-Bose crosses her arms, miming taking off a shirt], and men go over their shoulder, like in the shot. I’ve always found that somehow attractive, the difference between how some men and the women take their T-shirts off, these natural inclinations.

ED: That’s a very subtle, poetic detail about something that people might dismiss as mundane.

DCB: We actually shot that scene of him taking off his T-shirt more than any other scene in the film! Either the sky was too blue, or not blue enough. For whatever reason, taking off a T-shirt became a whole thing. [Laughter.]

ED: Another subtle detail about that shot of his neck is the silver chain he’s wearing — it gently helped place the scene in contemporary times, in the now. Because the T-shirt and one-piece are classic and could have been from almost any decade — 1970s, the 1940s.

Natasha Newman-Thomas, who is working with Keanu Reeves on an upcoming feature, is often tapped for her character-driven approach and vintage-inflected eye.

DCB: It definitely does make it contemporary.

ED: That sense of being in the now but also a bit not came through in many ways. The script features a lot of lines that have a certain dignity about them that feel of an older time; something about the score also feels closer to how music used to be featured in movies. And there’s that fantastic nod to Hitchcock’s 1958 film “Vertigo” in Chloë [Sevigny]’s hairstyle! But for me, that timelessness was especially conveyed with the costumes. Lots of full skirts, one-pieces, blouses with crisp collars, Lily’s black Repetto flats, and then an Adidas sweatshirt! Which, like the chain, redirects us back to the present. Was this sense of timelessness intentional?

DCB: I think it was the alchemy of several things. It wasn’t necessarily something that Miyako and I explicitly agreed on. It was her reading of the script, and, as you noted, the sort of mannered way that the characters spoke. I love that you called it “dignity.” It’s also worth noting that this film is an adaptation of a book from the 1950s, and layered over that is the first adaptation of the film by Otto Preminger, which came out shortly after the book. All of that created an orbit of ideas of timelessness. I always said to everyone involved in the film, “I don’t want this to just be the contemporary version of ‘Bonjour Tristesse.’” When I think about how to create that quality you mentioned, being out of step with time, how you create a world that makes the audience feel like they’re escaping from or forgetting the now, costume is a great way to do that.

ED: What’s an example?

DCB: Chloë’s character Anne is a fashion designer, but I wanted to establish her at a certain point in her career. I felt like, what would Cécile remember of her from that summer? The answer was a woman whose collars are really crisp.

ED: I love the idea of the crispness of a woman’s shirt collar being part of the storytelling. There’s a scene with a delicate lace coverlet on a bed that I’m thinking of, where Cécile’s dad, played by Claes Bang, and Chloë are making a bed together. The coverlet felt like it was part of the storytelling too: They’re creating something domestic together, something beautiful, but that is ultimately fragile as well. Was that the message in that scene?

DCB: I think my production team was interpreting what I wrote in the script and felt like that was the right material for that exchange between Anne and Raymond. It’s a scene where a man and a woman who share a very intense past are making a bed together, so describing that textile as “domestic” is right. It’s funny you bring up that coverlet, because the Balenciaga dress Chloë wore to our Toronto International Film Festival premiere was actually inspired by that scene.

ED: That’s amazing.

DCB: Chloë is always thinking about character, and she wants the choices that she makes in her own life to be part of a narrative. Narrative building is how she approaches acting, which I learned so much from. I love artists who are always thinking about the extent of their artistry in their actual life.

ED: Art imitates life but life also imitates art! Something about that coverlet must have felt important to her about her character.

DCB: We did a lot of what I’ll call fabric casting. The props team would show me various table settings for certain scenes; I’d talk with my cinematographer about it. Some of these decisions were actually purely technical — certain yellows just won’t look good on a terrace in the South of France at 3 p.m. Maybe these are boring details, but they were an education for me. You can’t just pursue aesthetic concepts.

ED: That’s a really important point. So much storytelling is conveyed in what might be considered a mundane, technical detail, yet that detail ends up creating a big impact.

DCB: Exactly. At the end of the film, Lily is wearing a red wool dress. It was in a light shade of red, but at the 11th hour when we were shooting, Miyako was like, “No, it’s not the right shade of red!” So she went out and found a wool dye.

ED: I love that! I read recently that the costume designer for the film “Conclave” hated the shade of red that cardinals wear today, that on screen it looked really tacky. So she dyed all of the cardinals’ costumes for the film a darker shade of red inspired by Renaissance portraits of cardinals. Like you said, big-picture aesthetic concepts dictate the costume design, but at the end of the day it also comes down to technical details that require a really sophisticated, experienced eye to perceive.

DCB: Totally. Miyako really has that eye. I think she’s also a world-builder. The anecdote about “Conclave” is interesting because clearly the costume designer wasn’t just wedded to fact and realism, but instead to world-building. Like within this story of what’s happening in this movie, the red wasn’t necessarily going to reflect reality. The way that characters talk in the script I wrote, we weren’t really seeking realism or trying to mimic the now in a way that people would respond to with relatability. That wasn’t going to be what drew them in. I wanted what drew them in to be something else, something that was achieved through world-building. Creating something that could feel like people knew where they were, but were also a bit unsure.

ED: That sounds like you’re describing what it’s like to be inside of a dream.

DCB: I love that. Early on, there was a conversation about how to capture Cécile’s interiority without using [voice-over] narration in the film, which is what the Preminger adaptation does. One of the marvels of the book is its first-person narration, and we wondered, “How do you do that on screen?” My hope is that the experience of watching it makes you ask, “Did this really happen, or is this how Cécile remembers it?” The way I wanted to reflect Cécile’s interiority was of those detailed moments that you commit to memory that change how you perceive womanhood, or love, or intimacy.

ED: Do you mean that the film represents Cécile’s memory?

DCB: It wasn’t some high-concept idea, I just think that generally if you’re making a movie that has to do with a young woman, in the summer, you’re immediately launched into memory more than you are into reality.

ED: I want to return to Chloë’s Balenciaga dress that was inspired by the coverlet. Maybe this is silly, but have you started dressing like any of the characters in the film?

DCB: No, that’s so interesting! I’ve definitely accumulated more vintage T-shirts since shooting “Bonjour,” but I also feel like there’s a quality to Cécile’s costume design that reminds me of myself at a younger age, like a slightly sporty edge to it.

ED: Sporty edge was totally your style in college.

DCB: That time on set, everyone kind of became their characters. Lily literally still wears black Repetto flats, the same that she wears in many scenes in “Bonjour.” It’s sort of like there’s an image that you can’t unsee. There’s no question, you kind of change with these sorts of big projects, and whatever that change is, I think for some people, it might be the way that they dress.

Eugenie Dalland is a writer and editor based in upstate New York. Her writing has appeared in BOMB, Hyperallergic, Los Angeles Review of Books and the Brooklyn Rail. She co-founded and published the arts and culture magazine Riot of Perfume from 2011 to 2019.